The Alien Kin

Diane Barbé & friends

various locations

ongoing

The Alien Kin is an experimental research and sound-performance project that explores non-verbal communication, collective musicality and biological imitation using handmade instruments as vehicles for embodiment. The sonic worlds of bogs, meadows, marshes, wetlands, but also deserts and periurban zones are listened and echoed through the making and the playing of the instruments.

The Alien Kin has been running since 2022 and has been performed in diverse places, with several key residencies that offered space to build the instruments, explore artisanal techniques, and develop the process. The project has taken different shapes and continues to grow.

🐦⬛ Download the project portfolio

2025

Research and instrument building residency at AADK, Blanca, Spain

Workshops and group performance during Campos de Martes, Centro Negra, Blanca, Spain

2024

Research and instrument building residency at Instituto Sacatar, Bahía, Brasil

Workshops and group performance at Ilha das Crianças, Itaparica, Bahía, Brasil

Workshop and group performance at Seanaps Festival, Leipzig, Germany

2023

Research and instrument building residency at 90mil Berlin, Germany

Group performance at VESSEL, 90mil Berlin, Germany

Research and instrument building residency at Grabowsee, Brandenburg, Germany Research and instrument building residency at Euphonia, Marseille, France

Group performance on Archipel Community Radio, 90mil Berlin, Germany

2022

Research and instrument building residency at Global Forest Kunstverein e.V., Schwarzwald, Germany Group performance at Vogelklang festival, Schwarzwald, Germany

Workshops and performance at Climate Care Festival, Floating University, Berlin, Germany

Recording sessions and group performance at Morphine Raum, Berlin, Germany

Human lives and ways of living cannot take place or be described in isolation; as all species become caught in the multilayered entanglements of the global economy, we become more and more aware of the disruption of human–animal interactions. The many voices, stories and sounds that compose these interactions all carry meaning, in the sense that they represent something to someone –the natural world is deeply semiotic and deeply sonorous.

The oldest fossils all reveal organs dedicated to making and receiving sounds, pointing to the crucial importance of listening and uttering in evolutionary processes. Research in anthropology and archaeology has extensively investigated the origins of sound-making practices in humans and other species, be they accidental, aesthetically-driven, or simply serendipitous; and some studies on the oldest known wind instruments (40,000 year old bone flutes) seem to imply that they may have been game calls, for deer or birds.

Whether considering the hunter who can imitate bird calls to attract them, or the vocal learning abilities of nightingales who pick up new songs throughout their entire life, the acoustics of particular ecosystems influence all musical practices. And when considering mimicry (a broader term that may include inaccurate, failed or misleading imitation), we are in fact dealing with deception—with the capacity of natural forms to create confusion, a playfulness at the thresholds of coherent analysis.

Timo Maran, in Mimicry and Meaning, points out that the “ability to perceive something as something else appears to have a strong linkage with illusion, belief, magic . . . and imagination” (2017). He insists that mimetic relations need to be understood not in general, but rather as a specific relation between three individuals (the mimic, the model, and the receiver, all linked through the mimetic sign). In this sense, sound mimicry should be understood more as “a multiplicity of things related by family resemblance rather than as a monolith,” according to the musicologist Emily Doolittle (Other Species’ Counterpoint—An Investigation of the Relationship between Human Music and Animal Song, 2007), or indeed as a game, driven or not by direct intentions.

For me, working with game calls is therefore at a crucial intersection that helps understand the kinds of relations that have been woven between humans and animals –hunting, sanctifying, revering, communicating, sacrificing. Doing so through sound, following Milla Tiainen, reminds us of the “distinctive capacity of sound to emerge in and establish relations.” (Milla Tiainen, “Sonic Technoecology,” Australian Feminist Studies 32, 2017).

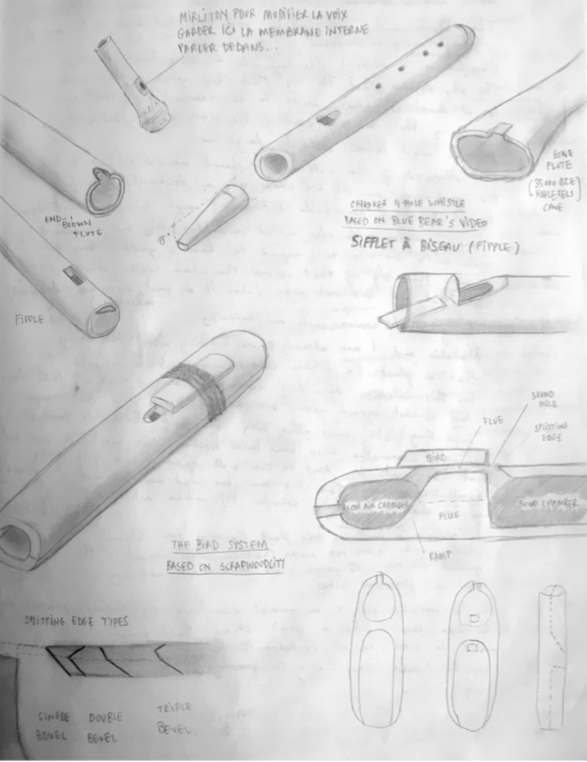

Working in the temperate Black Forest at the border between Germany, France and Switzerland, I became particularly interested in little sound devices usually called bird whistles or game calls in English, appeaux (“caller”) in French, and Wildlocker or Lockjagd in German. Game calls are most often wind instruments that use fipples or reeds to resonate hollow cavities, but they also include rattles, twisted pegs, membranes, and other ways to produce and amplify sound.

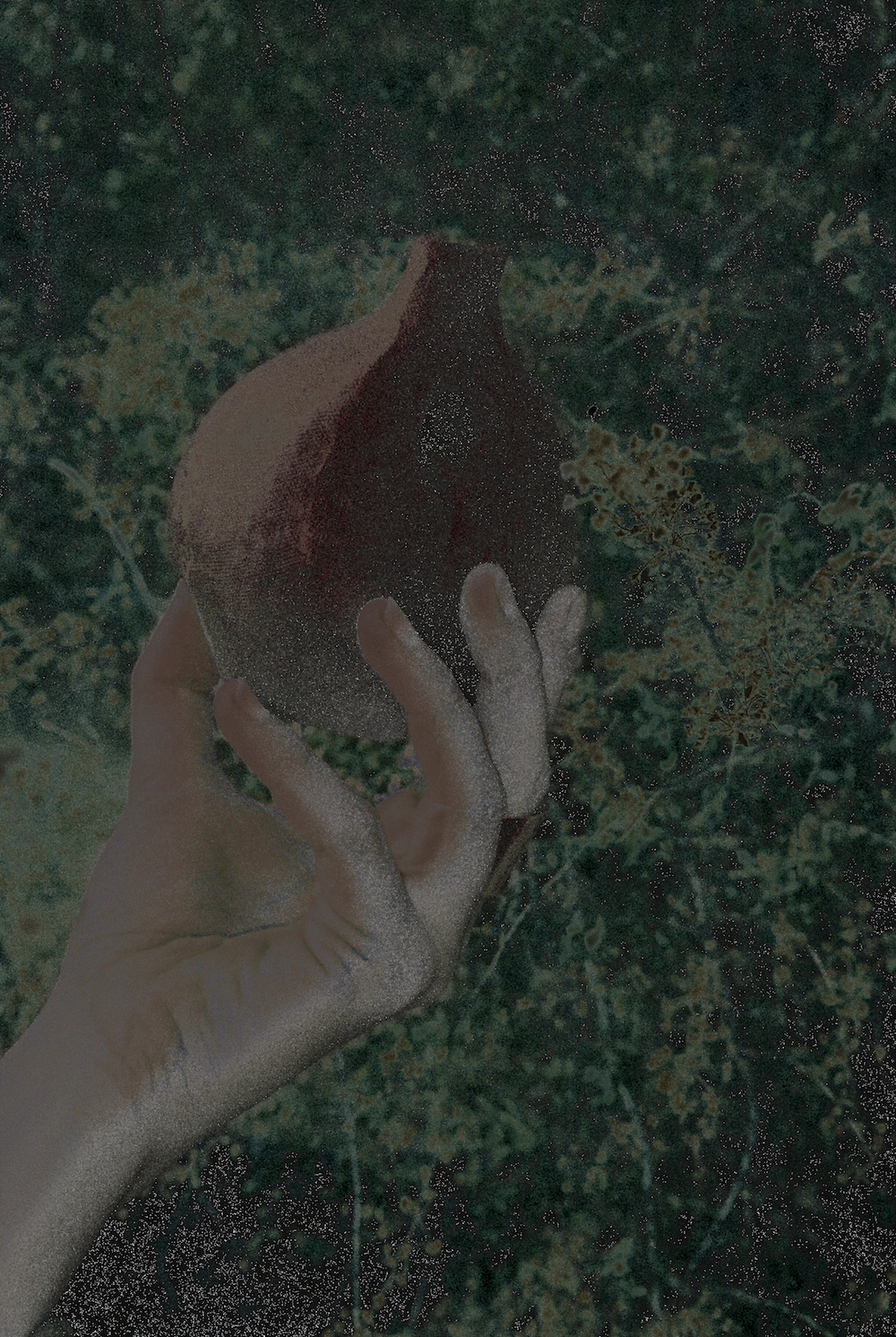

Little by little, I started to craft a collection of these sound devices: copper fipples, spruce recorders, “screaming” whistles, lamb bone edge flutes, rubber membrane geese callers… Later, I started to explore materials like river cane (Arundo Donax), also called the singing reed, a hollow bamboo-like reed which grows all around the Mediterranean and has been used for millenia to craft music instruments, both bodies of flutes (like the ney, the pan flute or the aulos) and wind reeds (like the duduk, the zurna, the clarinette, etc.). Then, I turned to clay, one of the oldest building materials, to explore its sonorities and different physical acoustics. I started harvesting wild clay and processing it; effectively, to quote Valéry, following the path of an animal transforming biological matter into mineral (L’Homme et la coquille, 1937). Globular vessels, to use another term than the limited “ocarina”, are found in ancient cultures throughout the world (and like bone, ceramic is one of the best-conserving materials that we can study).

When assembling the instruments, I choose to associate timbres and frequencies in ways that feel non-intrusive, non-standardized, and as easy to play as possible. I am inspired from Bernie Krause’s niche hypothesis in which different species vocalise in different frequency ranges and different rhythmical patterns to avoid interference and masking. In ensemble performances and workshops, we mainly work on the notions of synchronicity, space and dialogue: how do we inhabit, through sound? how do we call each other, or respond? how do we express an emotional state? how do we feel together as group, or disband as individuals? Most of the instruments are aerophones, which has immediate rhythmical implications since the players need to breathe. It is crucially interesting to wonder –at what point does a chaos of tweets start to feel like a meadow in the woods? When do we begin to “feel” patterns and imagine other bodies, other temporalities?

“Did imitative calls of other species assist our ancestors in hunting? . . . When exactly was it that a person was so adept at producing a call during a hunt that he was asked to do it again for the entertainment of others or taught it to his children as a life-skill?”

– Ian Nagoski, Ecstatic & Wingless: Bird-Imitation on Four Continents, ca. 1910-44, released October 2016, Canary Records

Publications

Albums, radio shows & writings

Podcast on L’Art de L’Écoute, Radio Grenouille

L’Art de l’Écoute is a long-standing evening of listening and experimental music, proposed by JB Imbert at Radio Grenouille, which is Marseille’s oldest and most diverse radio station. In this podcast, we talk (in French) about the first album of the Alien Kin: The Avian Kin, about to be released on tape and digital in November 2023, along with other questions related to mimicry, collective music, and field recording.

Podcast on L’Expérimentale, France Musique

L’Expérimentale, a France Musique podcast by François Bonnet, invited me to discuss biomimicry, intersspecies communication and polyphony. With music by David Rothenberg, Ann McMillan, Joan LaBarbara, Pablo Diserens, Bernard Fort, Maria Teresa Luciani, the Albanian polyphonic group Famille Lela de Permet & more (22 January 2023, 1h).

‘I Call, You Respond?’ in Pulse Journal

Pulse: the Journal of Science and Culture is an online, open-access, peer-reviewed journal, affiliated with the Central European University, Hungary. The journal’s aim is to become an innovative academic platform that fosters a dialogue between science studies and humanities, or science and culture, broadly taken. It therefore spans academic disciplines such as history, sociology and philosophy of science, cultural studies, medical and digital humanities, animal and environmental studies, cognitive studies, and extends to include diverse cultural media, such as fiction, film, performance, music, and other.

‘I Call, You Respond?: Game Calls, Hunting and Sound Mimicry in the Black Forest’, Pulse Journal, Vol. 9, 2022 (FASCINATING NOISE: SOUND IN ART AND SCIENCE). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10547158